Friday, March 4, 2011

proselytizing

I think i should just do yoga and not proselytize and I am sure many people share this view. So then why do I always feel compelled to suggest that people try yoga, convince my friends and known associates of its life transforming benefits, try to get more people to class? I don't really know the answer to this question but I'll try to come up with one nonetheless. I don't want to use big words and sound bathetic but of course I will. but yoga is a gift, and like pathabi jois said everyone, old man, young man, sick man, can benefit from the practice. or is there my ego lurking in the back and i just want to be proven right when i see a class full of student that i recruited? omg... the path to nirvana is long and hard.

Sunday, February 27, 2011

today's recipe

Today I have made a really nice cake with my little daughter. It is in my effort to make do without grains and flour, which we use too much in our diet. The cake is made with seeds, nuts and dried fruit. It is important that the dried fruit be organic (as in the non-organic varieties all kinds of horrible chemicals and additives are used). Here is the recipe: (use 1 tablespoon of everything unless otherwise noted.)

flaxseed

sunflower seeds

poppy seed

buckwheat flour (buckwheat is a seed)

almonds

hazelnuts

grind all the above into a fine flour-like consistency. Add:

2 tablespoons of cocoa powder

1 egg

canola oil or melted butter

2 tablespoons of honey

3 tablespoons of soy milk

dried raisins

dried cranberries

mix well, pour mixture in a well buttered pan, sprinkle with caster sugar, bake in hot oven for about 20 mins.

Saturday, February 19, 2011

The Yoga Tradition

The Yoga Tradition

by David Frawley (Vamadeva Shastri)

http://www.purifymind.com/YogaBudd.htm

By Yoga here we mean primarily the classical Yoga system as set forth by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. Patanjali taught an eightfold (ashtanga) system of Yoga emphasizing an integral spiritual development including ethical disciplines (Yama and Niyama), postures (Asana), breathing exercises (Pranayama), control of the senses (Pratyahara), concentration (Dharana), meditation (Dhyana) and absorption (Samadhi). This constitutes a complete and integral system of spiritual training.

By Yoga here we mean primarily the classical Yoga system as set forth by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. Patanjali taught an eightfold (ashtanga) system of Yoga emphasizing an integral spiritual development including ethical disciplines (Yama and Niyama), postures (Asana), breathing exercises (Pranayama), control of the senses (Pratyahara), concentration (Dharana), meditation (Dhyana) and absorption (Samadhi). This constitutes a complete and integral system of spiritual training.

However classical Yoga was part of the greater Hindu and Vedic tradition. Patanjali was not the inventor of Yoga, as many people in the West are inclined to believe, but only a compiler of the teaching at a later period. Yogic teachings covering all aspects of Patanjali Yoga are common in pre-Patanjali literature of the Puranas, Mahabharata and Upanishads, where the name Patanjali has yet to occur. The originator of the Yoga system is said to be Hiranyagarbha, who symbolizes the creative and evolutionary force in the universe, and is a form of the Vedic Sun God.

Yoga can be traced back to the Rig Veda itself, the oldest Hindu text which speaks about yoking our mind and insight to the Sun of Truth. Great teachers of early Yoga include the names of many famous Vedic sages like Vasishta, Yajnavalkya, and Jaigishavya. The greatest of the Yogis is always said to be Lord Krishna himself, whose Bhagavad Gita itself is called a Yoga Shastra or authoritative work on Yoga. Among Hindu deities it is Shiva who is the greatest of the Yogis or lord of Yoga, Yogeshvara. Hence a comparison of classical Yoga and Buddhism brings the greater issue of a comparison between Buddhist and Hindu teachings generally.

Unfortunately some misinformed people in the West have claimed that Yoga is not Hindu but is an independent or more universal tradition. They point out that the term Hindu does not appear in the Yoga Sutras, nor does the Yoga Sutra deal with the basic practices of Hinduism. Such readings are superficial. The Yoga Sutras abounds with technical terms of Hindu and Vedic philosophy, which its traditional commentaries and related literature explain in great detail. Another great early Yogic text, the Brihatyogi Yajnavalkya Smriti, describes Vedic mantras and practices along with Yogic practices of asana and pranayama. The same is true of the Yoga Upanishads. Those who try to study Yoga Sutras in isolation are bound to make mistakes. The Yoga Sutras, after all, is a Sutra work. Sutras are short statements, often incomplete sentences, that without any commentary often do not make sense or can be taken in a number of ways.

Other people in the West including several Yoga teachers state that Yoga is not a religion. This can also be misleading. Yoga is not part of any religious dogma proclaiming that there is only one God, church or savior, nor have the great Yoga teachers from India insisted that their students become Hindus, but Yoga is still a system from the Hindu religion. It clearly does deal with the nature of the soul, God and immortality, which are the main topics of religion throughout the world. Its main concern is religious and certainly not merely exercise or health.

Classical Yoga is one of the six schools of Vedic philosophy (sad darsanas) which accept the authority of the Vedas. Yoga is coupled with another of these six schools, the Samkhya system, which sets forth the cosmic principles (tattvas) that the Yogi seeks to realized. Nyaya and Vaisheshika, Purva Mimamsa and Uttara Mimamsa (also called Vedanta) are the remaining schools, set off in groups of two. Yoga is also closely aligned with Vedanta. Most of the great teachers who brought Yoga to the modern world, like Swami Vivekananda, Paramahansa Yogananda, Sri Aurobindo, and Swami Shivananda, were Vedantins.

These six Vedic systems were generally studied together. All adapted to some degree the methods and practices of Yoga. While we can find philosophical arguments and disputes between them, they all aim at unfolding the truth of the Vedas and differ mainly in details or levels of approach. All quote from Vedic texts, including the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita and Puranas for deriving their authority.

Some Western scholars call these "the six schools of Indian philosophy." This is a mistake. These schools only represent Vedic systems, not the non-Vedic of which they are several. In addition they only represent Vedic based philosophies of the classical era. There were many other Vedic and Hindu philosophical systems of later times.

by David Frawley (Vamadeva Shastri)

http://www.purifymind.com/YogaBudd.htm

By Yoga here we mean primarily the classical Yoga system as set forth by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. Patanjali taught an eightfold (ashtanga) system of Yoga emphasizing an integral spiritual development including ethical disciplines (Yama and Niyama), postures (Asana), breathing exercises (Pranayama), control of the senses (Pratyahara), concentration (Dharana), meditation (Dhyana) and absorption (Samadhi). This constitutes a complete and integral system of spiritual training.

By Yoga here we mean primarily the classical Yoga system as set forth by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. Patanjali taught an eightfold (ashtanga) system of Yoga emphasizing an integral spiritual development including ethical disciplines (Yama and Niyama), postures (Asana), breathing exercises (Pranayama), control of the senses (Pratyahara), concentration (Dharana), meditation (Dhyana) and absorption (Samadhi). This constitutes a complete and integral system of spiritual training. However classical Yoga was part of the greater Hindu and Vedic tradition. Patanjali was not the inventor of Yoga, as many people in the West are inclined to believe, but only a compiler of the teaching at a later period. Yogic teachings covering all aspects of Patanjali Yoga are common in pre-Patanjali literature of the Puranas, Mahabharata and Upanishads, where the name Patanjali has yet to occur. The originator of the Yoga system is said to be Hiranyagarbha, who symbolizes the creative and evolutionary force in the universe, and is a form of the Vedic Sun God.

Yoga can be traced back to the Rig Veda itself, the oldest Hindu text which speaks about yoking our mind and insight to the Sun of Truth. Great teachers of early Yoga include the names of many famous Vedic sages like Vasishta, Yajnavalkya, and Jaigishavya. The greatest of the Yogis is always said to be Lord Krishna himself, whose Bhagavad Gita itself is called a Yoga Shastra or authoritative work on Yoga. Among Hindu deities it is Shiva who is the greatest of the Yogis or lord of Yoga, Yogeshvara. Hence a comparison of classical Yoga and Buddhism brings the greater issue of a comparison between Buddhist and Hindu teachings generally.

Unfortunately some misinformed people in the West have claimed that Yoga is not Hindu but is an independent or more universal tradition. They point out that the term Hindu does not appear in the Yoga Sutras, nor does the Yoga Sutra deal with the basic practices of Hinduism. Such readings are superficial. The Yoga Sutras abounds with technical terms of Hindu and Vedic philosophy, which its traditional commentaries and related literature explain in great detail. Another great early Yogic text, the Brihatyogi Yajnavalkya Smriti, describes Vedic mantras and practices along with Yogic practices of asana and pranayama. The same is true of the Yoga Upanishads. Those who try to study Yoga Sutras in isolation are bound to make mistakes. The Yoga Sutras, after all, is a Sutra work. Sutras are short statements, often incomplete sentences, that without any commentary often do not make sense or can be taken in a number of ways.

Other people in the West including several Yoga teachers state that Yoga is not a religion. This can also be misleading. Yoga is not part of any religious dogma proclaiming that there is only one God, church or savior, nor have the great Yoga teachers from India insisted that their students become Hindus, but Yoga is still a system from the Hindu religion. It clearly does deal with the nature of the soul, God and immortality, which are the main topics of religion throughout the world. Its main concern is religious and certainly not merely exercise or health.

Classical Yoga is one of the six schools of Vedic philosophy (sad darsanas) which accept the authority of the Vedas. Yoga is coupled with another of these six schools, the Samkhya system, which sets forth the cosmic principles (tattvas) that the Yogi seeks to realized. Nyaya and Vaisheshika, Purva Mimamsa and Uttara Mimamsa (also called Vedanta) are the remaining schools, set off in groups of two. Yoga is also closely aligned with Vedanta. Most of the great teachers who brought Yoga to the modern world, like Swami Vivekananda, Paramahansa Yogananda, Sri Aurobindo, and Swami Shivananda, were Vedantins.

These six Vedic systems were generally studied together. All adapted to some degree the methods and practices of Yoga. While we can find philosophical arguments and disputes between them, they all aim at unfolding the truth of the Vedas and differ mainly in details or levels of approach. All quote from Vedic texts, including the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita and Puranas for deriving their authority.

Some Western scholars call these "the six schools of Indian philosophy." This is a mistake. These schools only represent Vedic systems, not the non-Vedic of which they are several. In addition they only represent Vedic based philosophies of the classical era. There were many other Vedic and Hindu philosophical systems of later times.

Sunday, February 13, 2011

ashtanga vs power yoga

This is Patthabi Jois on those who want to exploit the Ashtanga system to get rich and famous quick. I was particularly touched when he says:

The title "Power Yoga" itself degrades the depth, purpose, and method of the yoga system that I recieved from my guru, Sri T. Krishnamacharya. Power is the property of god. It is not something to be collected for one's ego. Partial yoga methods out of line with their internal purpose can build up the "six enemies" (desire, anger, greed, illusion, infatuation, and envy) around the heart. The full Ashtanga system practiced with devotion leads to freedom within one's heart.

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=iOkDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA6&lpg=PA6&dq=yoga+journal+december+1995+jois&source=bl&ots=c6pM3rXjHS&sig=zEWgsj6ySJ9bV581qyL-_1Rf5fc&hl=en&ei=Q0tKTcrhDc_wrQfM2fzuDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=iOkDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA6&lpg=PA6&dq=yoga+journal+december+1995+jois&source=bl&ots=c6pM3rXjHS&sig=zEWgsj6ySJ9bV581qyL-_1Rf5fc&hl=en&ei=Q0tKTcrhDc_wrQfM2fzuDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

Saturday, February 12, 2011

INHALE AND POSTURE

Pranayama, or breathing technique, is very important in yoga. It goes hand in hand with the asana or pose. In the Yoga Sutra, the practices of pranayama and asana are considered to be the highest form of purification and self discipline for the mind and the body, respectively. The practices produce the actual physical sensation of heat, called tapas, or the inner fire of purification. It is taught that this heat is part of the process of purifying the nadis, or subtle nerve channels of the body. This allows a more healthful state to be experienced and allows the mind to become more calm. As the yogi follows the proper rhythmic patterns of slow deep breathing "the patterns strengthen the respiratory system, soothe the nervous system and reduce craving. As desires and cravings diminish, the mind is set free and becomes a fit vehicle for concentration."

Today I was having yoga class with Adele. Sometimes it is a real struggle to get into a pose and stay in it with dignity. In these instances I start breathing really hard, hyperventillating. Today Adele admonished me for not having a long enough inhale. My exhales are good, she said, but there's not much to exhale if I inhale almost nothing.

In six years of practice I have never paid much attention to my inhale. In the second part of my practice I made a conscious effort to lengthen the breath especially the inhale. It makes a world of difference, I can now attest to that. I felt immediately calmer, and I stayed longer in the postures. In fact, I realized, that when you are already in the posture, it's best to just forget about it, and concentrate mostly on the breathing. I found that when I did that, the posture automatically took care of itself and got better, or deeper.

Today I was having yoga class with Adele. Sometimes it is a real struggle to get into a pose and stay in it with dignity. In these instances I start breathing really hard, hyperventillating. Today Adele admonished me for not having a long enough inhale. My exhales are good, she said, but there's not much to exhale if I inhale almost nothing.

In six years of practice I have never paid much attention to my inhale. In the second part of my practice I made a conscious effort to lengthen the breath especially the inhale. It makes a world of difference, I can now attest to that. I felt immediately calmer, and I stayed longer in the postures. In fact, I realized, that when you are already in the posture, it's best to just forget about it, and concentrate mostly on the breathing. I found that when I did that, the posture automatically took care of itself and got better, or deeper.

Friday, February 11, 2011

giving

1. Ahimsa – Compassion for all living things

The word ahimsa literally mean not to injure or show cruelty to any creature or any person in any way whatsoever. Ahimsa is, however, more than just lack of violence as adapted in yoga. It means kindness, friendliness, and thoughtful consideration of other people and things. It also has to do with our duties and responsibilities too.

The word ahimsa literally mean not to injure or show cruelty to any creature or any person in any way whatsoever. Ahimsa is, however, more than just lack of violence as adapted in yoga. It means kindness, friendliness, and thoughtful consideration of other people and things. It also has to do with our duties and responsibilities too.

http://www.facebook.com/#!/video/video.php?v=1378237514624&comments

Monday, January 31, 2011

Ashtanga yoga in Tallinn

I remember Tallinn very well. I went there over 15 years ago and spent a week, wandering the enchanting medieval streets during the day and talking to my ethnic Russian landlady in my rudimental Russian at night. I will never forget that city at that time, just waking up after long decades of communism and Russian rule, trying to figure out its place in the new order.

I have seen this absolutely beautiful video recently on Youtube posted by a guy named Jock who follows my guru Lino Miele and has his own Ashtanga school in the Estonian capital. I hope to go back to Tallinn sometime soon, see the changes the city has gone through since I last went there, and practice with Jock, who seems an overall nice and interesting guy. What I find nice about the internet is that you can create these virtual relationships in the yoga world that are nonetheless relationships and which one day can come true.

Here is the vid, enjoy, relax by just watching and listening.

Here is the vid, enjoy, relax by just watching and listening.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Seeds

Today I have celebrated my 30th day of being a vegetarian. Sometimes yes, I wish I could have a beautiful slice of prociutto crudo. I miss seafood and steak. But as someone who is dearest to my heart, a vegetarian himself, said, being a vegetarian just makes you a better person, calmer, less agressive, and more healthy. It's a moral choice we can make and sets us, humans, apart from the beasts. And I totally agree with him. Of course, I want to avoid becoming a self-righteous ass who judges meat eaters and feels superior to them. But I do believe that somehow doing away with meat makes you a better person. I have developed this weird theory - and I'm sure it's not new at all - that when you eat meat, you really eat suffering. When an animal is slaughtered it suffers, not to mention the kind of constricted, inhumane, albeit short life these poor critters are forced to lead.

For me vegetarianism is also a huge challenge. I want to eat interestingly, not just boring salads and veggie soups. It is also important not to overdo the bread and cereal angle as many vegetarians do. And do I get enough protein in my diet? is another concern. What about iron? As I get more and more sucked into the whole vegetarian biz on the internet, I discover the various sub-fads as well, raw foodism, veganism, non-grain eaterism, paleo-vegetarianism, fruitarianism etc. But all this also makes life more interesting right now as I put more brainwork into what I put into my mouth.

“If animals died to fill my plate, my head and my heart would become heavy with sadness”, says Guruji. “Becoming a vegetarian is the way to live in harmony with animals and the planet.”

Monday, January 24, 2011

compulsive shopper

my compulsive shopping habit... hmmm... a long time ago, in another lifetime, my now ex husband cut up my charge and credit cards in a rage when he realized that i had maxed out on all of them in one month and spent my monthly salary a couple of times over on stupid stuff i could not even find anymore among all the other stuff that i had purchased previously. i have never had credit cards since, but i have never had any money put aside for a rainy day in the bank either, and even though i have always worked hard and earned well, i have also always been totally broke. but my wardrobe... my bookshelves, my jewelry chest, my bathroom... full of STUFF... STUFF and more STUFF. i have 35 pairs of blue jeans. 15 pairs of black jeans. i have green jeans, pink jeans, purple jeans, grey jeans, white jeans. that's just jeans.

i won't go into linen pants, leather pants, dressy woolen pants, leggings, corduroy slacks, shorts, silk trousers, etc. i have a hundred skirts. i have boots in all the colors of the rainbow. i have dozens of leather bags. thousands of books. tons of bling. i don't even know what i have. and I am not Carrie Bradshaw or whoever just a simple woman trying to live the yogi life.

but what is actually worse than having all this stuff is the yearning for more. this constant desire, longing, craving for more stuff. wanting another pair of pants, this time shorter and tighter, hungering for another t-shirt or yet another pair of dr martens, the cool 18-eyelet model in the weird antique rose color. keeping my eye on the latest book of my favorite author(s), lusting for another bag or purse or pocketbook or backpack, some more trinkets or the umpteenth lipstick etc., etc...

i don't know where my tendency to buy buy buy and my desire to hoard more come from, probably some deep seated psychological trauma back before i was conceived. but i do know that by desiring and hoarding stuff i am breaking one of the 8 rules of yoga, Aparigraha - Neutralizing the desire to acquire and hoard wealth, that is part of YAMA.

Aparigraha means to take only what is necessary, and not to take advantage of a situation or act greedy. It also implies letting go of our attachments to things and an understanding that impermanence and change are the only constants.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

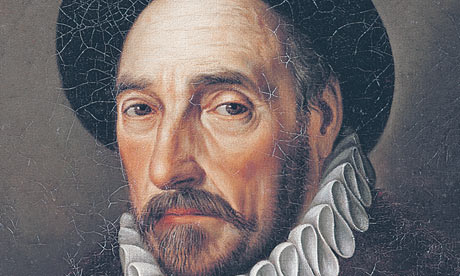

Montaigne and the macaques

Today I would like to publish Saul Frampton's recent article in the Guardian. I am not sure how it relates to the 8 limbs of yoga, but I think it does.

Montaigne and the macaques

Saturday, January 22, 2011

SNOW, iPOD AND YOGA

This morning my car was hidden under a pile of snow. This is only interesting because I live near Rome where it rarely snows. But then I live on the Monte Cavo, 700 meters above sea level.

|

| Monte Cavo with the Albano Lake |

So sometimes it snows. By the time I get down to the next town, the snow becomes slush then rain. It's like living in my own micro-climate and I like it.

I wanted to practice this morning so last night I set my alarm at 6 o'clock. I wonder how it happened, but I don't remember hearing and then turning off the alarm.When I next opened my eyes it was 7.30. The first thing I saw was the grey grey snow through my bedroom window. I didn't so much feel like getting out of bed and practicing. Instead I took a pint of coffee into my bedroom, checked my twitter account and I read an interesting post about new German eugenics laws.

Tonight I tried to fix my new iPod but I don't think I am cut out for these state of the art technological gizmos. I did manage to somehow transfer all my yoga, meditation and om music onto it, which is cool. As soon as spring springs on us, I will meditate with Mr. Pod on the Albano lake.

I finally did do my practice tonight. I suggested that we all practice together, the whole family, and we did. It was a lot of fun, and really nice. I didn't do full vinyasa but it was still ok. I find this whole full vinyasa business a little disturbing. I know full vinyasa is the real thing and that's what I should do every day. But I find it really difficult to do, really hard on my body, and it also takes very long, almost two hours, which I rarely have. So often I end up not practicing at all because I chicken out of doing full vinyasa. I think I have to work at it. Go back to doing half vinyasa, and sometimes, when I feel like it, and have the time, do full. Just relax and take it as it comes. I think that's what I'll do.

After the practice we had a nice supper. It was literally supper, as the word comes from soup. So there was cream of white bean and pumpkin soup with my favorite bread, which is made with stone ground whole wheat flour and no salt. On the bread I put my walnut cheese spread and a little Casa Giulia fig jam.

Walnut Cheese Spread

|

Ingredients:

100 grams walnut

100 grams blue cheese

200 grams low fat cream cheese

lots of freshly ground pepper

Instructions:

Using a hand held mixer, mix (blend well) all ingredients together and refrigerate for a couple of hours.

Thursday, January 20, 2011

new years resolutions

did yoga this morning. tried monkey pose (Hanumanasana), getting there, sort of half way.

this year i have made two new year's resolutions. 1. become a vegetarian. 2. stop shopping and splurging. for some reason i though becoming a vegetarian would be difficult whileas control shopping easy. it's precisely the other way round. i find vegetarianism fun challenging, and i've been feeling good, full of energy since i stopped eating meat. shopping is easy just loads of fresh healthy stuff. i'm really into soy and seitan products now, experimenting.

it's harder to resist shopping. esp when the sales are on. i realize the prob is big, huge. some kind of addiction disorder. question is why me. and how to deal with it. sheer will power? do i have that? so far not so good, anyway. a despicable, disastrous failure, is what i've been. and the mind... the mind is kinda hard to stop. tomorrow i'm not gonna check out those ultra cool black leather pants 75% off i've been obsessed with for the last week.

I could look like this above. Hmmm. almost anyway.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

haven't been practicing

For some reason I haven't been practicing for the past few days and I miss the yoga. I am too tired to get up early enough in the morning, the only time I can practice. I usually get up at 5 and practice between 5.30 and 7. From 7 on everyday life and craziness starts, I have to get ready to go to work and get my little daughter ready as well, and start the day at the school at 8.30 the latest. In the evening I am too tired to practice.

Tomorrow is another day. I intend to go to sleep early tonight and get up early tomorrow to practice.

Tomorrow is another day. I intend to go to sleep early tonight and get up early tomorrow to practice.

Sunday, January 16, 2011

a lazy sunday

today i have worked on designing my blog. i am totally not cut out for this. even though i am sure it is made for fools and the software is real user-friendly, i have spent a lot of time just trying to figure out what to do and how. i am still not satisfied with the result.

i have also cooked a nice vegetarian lunch, which we are going to wolf down in a moment. there will be cream of brussels sprout and lima bean soup, vegetarian chopped liver on whole wheat toast (for recipe: http://kidscooking.about.com/od/snacksdipsappetizers/r/mock-chopped-liver-recipe.htm) and greek salad. it is a beautiful sunny day outside so well probably go and have an icecream after lunch.

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

the first day

today is my first day of blogging and i must admit i am totally new to this. i am doing this for myself, not to provide inspiration for other people. it is part of self study, or Svadhyaya, which is part of Niyama, the second limb of yoga.

When i discovered what yoga really meant, all the eight limbs, i felt exhilirated because i sensed that it would finally be the path, some kind of guidance, as to how to try to live. i have this theory that life is nothing except an awful amount of time until you die, that it has no sense or meaning, but somehow you have to give it both and structure the time until its time to exit so you dont keel over of boredom.

i was brought up outside religion, spirituality, or any framework of ritual. i have never been taught to pray or convinced that god existed. it is still difficult for me to comprehend that there is a divine or what it is, let alone meditate on or unite with it, which are the 7th and 8th limbs of yoga. i am not that far yet and i dont know if i ever will be. but i am kind of curious to see what would happen if i ever did get there.

When i discovered what yoga really meant, all the eight limbs, i felt exhilirated because i sensed that it would finally be the path, some kind of guidance, as to how to try to live. i have this theory that life is nothing except an awful amount of time until you die, that it has no sense or meaning, but somehow you have to give it both and structure the time until its time to exit so you dont keel over of boredom.

i was brought up outside religion, spirituality, or any framework of ritual. i have never been taught to pray or convinced that god existed. it is still difficult for me to comprehend that there is a divine or what it is, let alone meditate on or unite with it, which are the 7th and 8th limbs of yoga. i am not that far yet and i dont know if i ever will be. but i am kind of curious to see what would happen if i ever did get there.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)